Saturday, October 31, 2009

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Thursday, October 15, 2009

One Day in October

October 17, 1989 was a special day, for it was the occasion of the first World Series game to be played in San Francisco since 1962. To make it even more interesting, the Giants would be playing their cross bay rivals, the Oakland A's. I'd been looking forward to it for weeks.

As I walked to work through the busy streets of the city that afternoon, it seemed like every car I passed had its windows open and its radio on and that every radio was tuned to the game.

The day was hot and dry. There was absolutely no breeze. The heat had a heavy quality particular to fall. As I walked, I heard a woman say, “this feels like earthquake weather.”

We know that there is no connection between earthquakes and the weather, but on that day, that woman proved prophetic. At 5:04 that afternoon, the Loma Prieta Earthquake struck.

Most people will tell you that they were in the midst of their normal routine that day. I know I was. The only unusual thing I did that day was to bring a T.V. to work in order to watch the game.

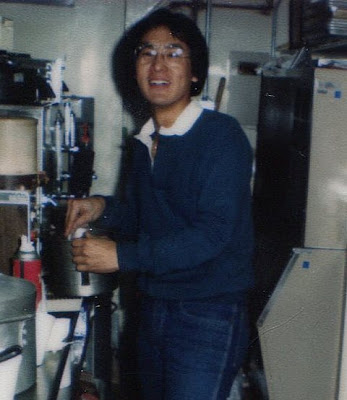

In those days, I owned my own businesses.

My partners and I owned three stores: two Double Rainbow Ice Cream franchises

and a coffee store called Designer Beans.

That afternoon, I was working at our Double Rainbow store near Union Square in San Francisco.

When I got to work, I put the TV behind the counter so that everyone could see it.

Just before the game started, the earthquake hit.

In the store, we felt one large jolt. A bottle of Italian soda syrup fell off a shelf.

The power went out.

Then, it was over.

I’d been through many earthquakes before, so I didn’t think much of this one. After all, We'd only lost one bottle off of a shelf lined with them.

Not everyone had the same reaction. People came streaming out of the Holiday Inn across the street. Many of them had left in a hurry. They stood, in a daze, on the sidewalk, some in bathrobes and slippers. Soon, the sidewalk was filled with people from other buildings in the neighborhood, all looking worried and confused.

Upon seeing this, one of my employees looked at me and grinned.

“Tourists,” he snickered.

Despite the power outage, the TV continued to work, because it could run on batteries, but the screen was black. No sound either. We suddenly felt cut off.

After a few minutes, TV stations went back on the air. They’d lost power too, but had switched to emergency generators in order to go back on the air.

The first pictures we saw were of fans, players, umpires and police standing together on the playing field at Candlestick Park.

The TV announcer, Al Michaels, lived in the Bay Area. He handled the situation in an calm, relaxed manner, for he too had been through many earthquakes. When the quake hit, he continued broadcasting. He simply changed the subject from baseball to earthquakes.

Johnny Bench, a Hall of Fame catcher who was doing the radio broadcast, had not been through an earthquake before. When it hit, he jumped out of his chair and ran for the nearest steel doorway. Later his broadcast partner, Jack Buck, told him, “If you moved that fast when you played, you wouldn’t have hit into so many double plays.”

Back at the store, our first indication that this earthquake was more serious than we thought was when Al Michaels announced that Candlestick Park was being evacuated due to possible damage to the structure. The channel then switched to a shot of the Bay Bridge, where one section of the roadway collapsed.

My store stayed open. We were one of the few that did. Many of the people milling around on the street came in as if to seek refuge from a storm.

We sold them ice cream, baked goods and rapidly cooling coffee. Some customers tried to hoard food by trying to buy whole loaves of banana bread or lemon cake. We had to impose a two slice per person limit.

One of my workers arrived for her 6 o’clock shift. With wide eyes, she told me that she was at her school, St. Rose Academy, when the quake hit. She was walking across the yard.

“The ground rolled across the blacktop like a wave,” she said.

Customers stayed to watch my 5” TV. It was their only source of information. Everyone crowded into one corner of the store. As it got dark outside, they stayed, attracted to the TV like moths to a flame.

At first, all we saw were shots of the Bay Bridge. Then we saw shots of collapsed or burning buildings in the Marina District.

My sister lived in the Marina. I began to worry.

Then we saw a shot of a collapsed freeway in Oakland.

The crowd let out a collective gasp.

Night fell. The power remained out. Our emergency lights were on, so we stayed open just to let people watch TV.

We ran out of baked goods and coffee.

Nobody was in the mood for ice cream.

After the crowd thinned out we closed the store.

My next challenge was to get home. I lived about 20 miles away in the East Bay and used the Bay Bridge every day. That night, I had to drive through the darkened city into Marin and then over the Richmond Bridge in order to get home. All of the traffic signals were out, but traffic was surprisingly orderly. Still, it took me over an 2 hours to make what was normally a 45 minute drive.

My house had power. I turned to lights on to find my bookshelves toppled and everything that was on them scattered all over the floor. As I surveyed the damage, my cats came out from wherever they were hiding, rubbed against my leg and yowled at me as it to say, “Where the heck have you been?

The ice cream store didn’t get power back for two days. We packed the ice cream in dry ice to try to save it, but eventually had to throw out about 30 gallons of the stuff.

Game 3 of the World Series was postponed for 10 days. The A's won. They also won game 4 the following day to complete a sweep.

My sister wasn't hurt and her building sustained no damage.

The damage at St. Rose Academy was so extensive that it had to close. The building is boarded up to this day. The school eventually reopened at a new location.

As I walked to work through the busy streets of the city that afternoon, it seemed like every car I passed had its windows open and its radio on and that every radio was tuned to the game.

The day was hot and dry. There was absolutely no breeze. The heat had a heavy quality particular to fall. As I walked, I heard a woman say, “this feels like earthquake weather.”

We know that there is no connection between earthquakes and the weather, but on that day, that woman proved prophetic. At 5:04 that afternoon, the Loma Prieta Earthquake struck.

Most people will tell you that they were in the midst of their normal routine that day. I know I was. The only unusual thing I did that day was to bring a T.V. to work in order to watch the game.

In those days, I owned my own businesses.

My partners and I owned three stores: two Double Rainbow Ice Cream franchises

and a coffee store called Designer Beans.

That afternoon, I was working at our Double Rainbow store near Union Square in San Francisco.

When I got to work, I put the TV behind the counter so that everyone could see it.

Just before the game started, the earthquake hit.

In the store, we felt one large jolt. A bottle of Italian soda syrup fell off a shelf.

The power went out.

Then, it was over.

I’d been through many earthquakes before, so I didn’t think much of this one. After all, We'd only lost one bottle off of a shelf lined with them.

Not everyone had the same reaction. People came streaming out of the Holiday Inn across the street. Many of them had left in a hurry. They stood, in a daze, on the sidewalk, some in bathrobes and slippers. Soon, the sidewalk was filled with people from other buildings in the neighborhood, all looking worried and confused.

Upon seeing this, one of my employees looked at me and grinned.

“Tourists,” he snickered.

Despite the power outage, the TV continued to work, because it could run on batteries, but the screen was black. No sound either. We suddenly felt cut off.

After a few minutes, TV stations went back on the air. They’d lost power too, but had switched to emergency generators in order to go back on the air.

The first pictures we saw were of fans, players, umpires and police standing together on the playing field at Candlestick Park.

The TV announcer, Al Michaels, lived in the Bay Area. He handled the situation in an calm, relaxed manner, for he too had been through many earthquakes. When the quake hit, he continued broadcasting. He simply changed the subject from baseball to earthquakes.

Johnny Bench, a Hall of Fame catcher who was doing the radio broadcast, had not been through an earthquake before. When it hit, he jumped out of his chair and ran for the nearest steel doorway. Later his broadcast partner, Jack Buck, told him, “If you moved that fast when you played, you wouldn’t have hit into so many double plays.”

Back at the store, our first indication that this earthquake was more serious than we thought was when Al Michaels announced that Candlestick Park was being evacuated due to possible damage to the structure. The channel then switched to a shot of the Bay Bridge, where one section of the roadway collapsed.

My store stayed open. We were one of the few that did. Many of the people milling around on the street came in as if to seek refuge from a storm.

We sold them ice cream, baked goods and rapidly cooling coffee. Some customers tried to hoard food by trying to buy whole loaves of banana bread or lemon cake. We had to impose a two slice per person limit.

One of my workers arrived for her 6 o’clock shift. With wide eyes, she told me that she was at her school, St. Rose Academy, when the quake hit. She was walking across the yard.

“The ground rolled across the blacktop like a wave,” she said.

Customers stayed to watch my 5” TV. It was their only source of information. Everyone crowded into one corner of the store. As it got dark outside, they stayed, attracted to the TV like moths to a flame.

At first, all we saw were shots of the Bay Bridge. Then we saw shots of collapsed or burning buildings in the Marina District.

My sister lived in the Marina. I began to worry.

Then we saw a shot of a collapsed freeway in Oakland.

The crowd let out a collective gasp.

Night fell. The power remained out. Our emergency lights were on, so we stayed open just to let people watch TV.

We ran out of baked goods and coffee.

Nobody was in the mood for ice cream.

After the crowd thinned out we closed the store.

My next challenge was to get home. I lived about 20 miles away in the East Bay and used the Bay Bridge every day. That night, I had to drive through the darkened city into Marin and then over the Richmond Bridge in order to get home. All of the traffic signals were out, but traffic was surprisingly orderly. Still, it took me over an 2 hours to make what was normally a 45 minute drive.

My house had power. I turned to lights on to find my bookshelves toppled and everything that was on them scattered all over the floor. As I surveyed the damage, my cats came out from wherever they were hiding, rubbed against my leg and yowled at me as it to say, “Where the heck have you been?

The ice cream store didn’t get power back for two days. We packed the ice cream in dry ice to try to save it, but eventually had to throw out about 30 gallons of the stuff.

Game 3 of the World Series was postponed for 10 days. The A's won. They also won game 4 the following day to complete a sweep.

My sister wasn't hurt and her building sustained no damage.

The damage at St. Rose Academy was so extensive that it had to close. The building is boarded up to this day. The school eventually reopened at a new location.

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Mill Valley Jack in the Box, R.I.P.

Whenever you ride down Miller Ave you may notice a forlorn, out of place little building near Whole Foods that used to be a Jack in the Box fast food restaurant.

In recent years it's always seemed like a lonely place, a throw back to another era being visited by almost nobody. I, however, remember it when it was new. It's where I got my first real job.

When I was a high school junior all of my friends had flashy bikes. One even traveled to Italy to have one custom built for him. I wanted an Italian bike too. I'd even picked one out. It was a lime green Italvega

with a steel Columbus frame and a mix of Campagnolo,

Stronglight and Mafac components.

Very exotic, and for me, very expensive at $200 (today an equivalent bike would cost over $3000). So, in order to buy this bike, I needed to get a job.

One day, I decided to apply for a job at the Jack in the Box. I hopped on my beater bike and rode down from Homestead Valley. When I was about halfway there, it started to rain. I got soaked. I had a choice: continue on and apply for a job while all wet, or go back home and try again another day? I continued on.

When the manager saw me, he shook his head, smiled slightly and gave me an application. After I turned it in he told me that he didn't have any openings but would call me when one came up.

He called me back that night.

Later, he told me he hired me because anyone who was willing to ride his bike in the rain to apply for a job deserved to have one.

Anyway, I soon found myself working on Friday, Saturday and Sundays. Since I was the new guy I got all of the lousy shifts. On Fridays and Saturdays I worked from 6 p.m til 2 in the morning. Sometimes I worked from 7 p.m. til 3.

The store didn't do much business after 9, so I spent most of my shift cleaning up the store and restocking it for the next day by doing such things as slicing tomatoes, onions and lettuce.

For our safety, we locked the dining room at 10 p.m. It's a good thing we did, too, because the later it got, the stranger our customers were.

For one thing, we'd get a rush of customers every night (early morning, really) just after 2 a.m., which is when bars close. These customers were mostly from the nearest bar, the 2 A.M. Club. Let's just say that many of those people shouldn't have been driving.

One night, four high school boys walked up the entrance at around 11. We told them the dining room was closed. They left. A minute later, the bell sounded, indicating that there was a car waiting to place an order. We took the order, then waited for the car to drive up. There was no car. It was the boys.

The boys came up to the window in two rows of two as if they were in a car. They were all in a half crouch and the one closest to the window had his hands up as if he were holding a steering wheel. When we handed him his order, he pretended to roll down his window, handed us his money, reached up to get his food, handed it to the guy next to him, rolled up his window and, with his hands still holding the wheel and with his friends still in formation, "drove" off.

At around midnight each night another worker would show up for his 12 - 8 graveyard shift. His name was Matt. He was the same age as me. He eventually was elected class president at Tam and is now a prominent lawyer. Back then, he was kind of the class clown.

One night while I was in the back slicing tomatoes a customer walked up to the drive through window. I never saw him, for Matt took his order, but I did hear Matt's side of the conversation. It went something like this:

"Hi, can I help you?"

(unintelligible reply)

"Sorry man, I can't do that. How about a nice Jumbo Jack?"

(louder, but still unintelligible reply)

"Look, I'm really busy. Do you want some food or not?"

When I heard that, I came out of the back to see what was going on, but the customer was gone.

"What was that all about?", I asked Matt.

"It was nothing," replied Matt, "just some guy trying to rob us."

All in all, it was a pretty fun job. Learned how to cook real fast, work a cash register and deal with the public. These were all skills that would come in handy as I grew up. Oh, and I got paid, too. My wage? $1.65 per hour.

In recent years it's always seemed like a lonely place, a throw back to another era being visited by almost nobody. I, however, remember it when it was new. It's where I got my first real job.

When I was a high school junior all of my friends had flashy bikes. One even traveled to Italy to have one custom built for him. I wanted an Italian bike too. I'd even picked one out. It was a lime green Italvega

with a steel Columbus frame and a mix of Campagnolo,

Stronglight and Mafac components.

Very exotic, and for me, very expensive at $200 (today an equivalent bike would cost over $3000). So, in order to buy this bike, I needed to get a job.

One day, I decided to apply for a job at the Jack in the Box. I hopped on my beater bike and rode down from Homestead Valley. When I was about halfway there, it started to rain. I got soaked. I had a choice: continue on and apply for a job while all wet, or go back home and try again another day? I continued on.

When the manager saw me, he shook his head, smiled slightly and gave me an application. After I turned it in he told me that he didn't have any openings but would call me when one came up.

He called me back that night.

Later, he told me he hired me because anyone who was willing to ride his bike in the rain to apply for a job deserved to have one.

Anyway, I soon found myself working on Friday, Saturday and Sundays. Since I was the new guy I got all of the lousy shifts. On Fridays and Saturdays I worked from 6 p.m til 2 in the morning. Sometimes I worked from 7 p.m. til 3.

The store didn't do much business after 9, so I spent most of my shift cleaning up the store and restocking it for the next day by doing such things as slicing tomatoes, onions and lettuce.

For our safety, we locked the dining room at 10 p.m. It's a good thing we did, too, because the later it got, the stranger our customers were.

For one thing, we'd get a rush of customers every night (early morning, really) just after 2 a.m., which is when bars close. These customers were mostly from the nearest bar, the 2 A.M. Club. Let's just say that many of those people shouldn't have been driving.

One night, four high school boys walked up the entrance at around 11. We told them the dining room was closed. They left. A minute later, the bell sounded, indicating that there was a car waiting to place an order. We took the order, then waited for the car to drive up. There was no car. It was the boys.

The boys came up to the window in two rows of two as if they were in a car. They were all in a half crouch and the one closest to the window had his hands up as if he were holding a steering wheel. When we handed him his order, he pretended to roll down his window, handed us his money, reached up to get his food, handed it to the guy next to him, rolled up his window and, with his hands still holding the wheel and with his friends still in formation, "drove" off.

At around midnight each night another worker would show up for his 12 - 8 graveyard shift. His name was Matt. He was the same age as me. He eventually was elected class president at Tam and is now a prominent lawyer. Back then, he was kind of the class clown.

One night while I was in the back slicing tomatoes a customer walked up to the drive through window. I never saw him, for Matt took his order, but I did hear Matt's side of the conversation. It went something like this:

"Hi, can I help you?"

(unintelligible reply)

"Sorry man, I can't do that. How about a nice Jumbo Jack?"

(louder, but still unintelligible reply)

"Look, I'm really busy. Do you want some food or not?"

When I heard that, I came out of the back to see what was going on, but the customer was gone.

"What was that all about?", I asked Matt.

"It was nothing," replied Matt, "just some guy trying to rob us."

All in all, it was a pretty fun job. Learned how to cook real fast, work a cash register and deal with the public. These were all skills that would come in handy as I grew up. Oh, and I got paid, too. My wage? $1.65 per hour.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)